At the cafe Charifa I get to know Otman and Said: two gentle souls. Otman brings me to walk around the city when he isn’t working. We share some lunches and dinners, another time he takes me to a distant market and then to a graveyard where his girlfriend rests, dead barely a year ago. On a Sunday he brings me to see his family and I share a delicious Moroccan meal with Otman, his mother, his sister, their aunt and her husband. We then walk half the way back, seven kilometers of city that didn’t exist when Otman was growing up; he tells me about the fields and the flowers that were there before. We buy fresh pomegranate juice on the street and the bittersweet heaviness on my tongue contrasts well with the wide setting sun, blinding me.

I enjoy walking with Otman; he isn’t too talkative and at times we share long and relaxed silences, yet he generously answers all my questions about the city and its history and he is not shy when he tells me about his life and childhood. Everything about him is kindness; it is seeping out just by the way he looks at the world. He stops to give a coin to people asking on the streets, he feeds the cat frequenting the cafe and he is friends with a dog at the graveyard to whom he always brings a piece of mortadella every week. We walk through the mud and among the many similar gravestones he finds the right one. He places his hand on it as if it was a shoulder of a friend he was trying to comfort. He has to lean forward as he does this. I stand silently next to him. A man comes to us and reads prayers. When he is finished, Otman tips him generously.

I go often to the cafe to write or to make video calls and after a while my money is refused when I try to pay for my teas. I have to dance and play-fight and in the end I manage to stick the crumpled up ball of 20 dirham into Saids front pocket even as he holds up his hands and laughs. I am invited to lunches and dinners: couscous, tajin, cooked beans and potatoes that we sometimes eat at the table all together (other guests are always invited) or sitting on low stools hidden behind the high counter.

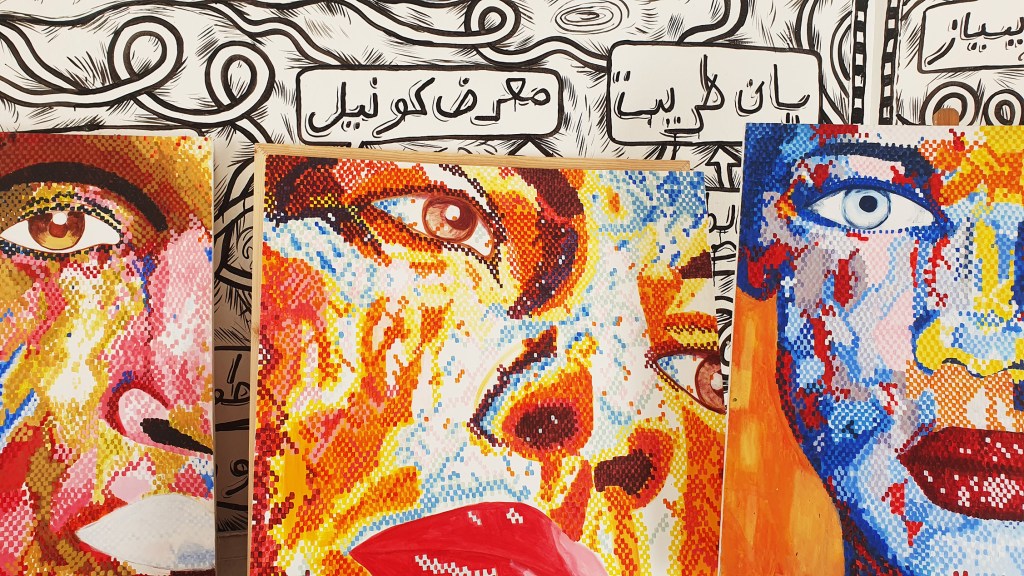

Said is an artist and his bright portraits pop out from the black-and-white painted patterns at cafe Cherifa. When the work is slow he works on his art, currently focusing most of his time on a portrait of his neighbour’s three children. Or he leans out of the window and looks down at the Medina and the seagulls passing. At one time he tells me that he wants to burn all of his paintings.

“Why?” I ask him, upset in my voice. He laughs then, and answers with a mischevious smile.

“Oh I want to do it with an audience and journalists present,” he says. Then I think I can see it, his vision: a big bonfire, Said throwing the beautiful canvases into the fire, the faces going up in flames, colors melting. It would be like a performance; I see the power of his vision.

Cafe Cherifa becomes my living room and creative womb. It is not noisy and full of smoke like the other cafes, there is no TV but the speakers play either blues or traditional Moroccan music when they are on and I come to realize that I need a place like this. Here, writing is effortless and I feel like home when I am met with smiles on my arrival and with a “see you tomorrow” as I leave.

…

(This story told in pictures.)

The artist is Said.