I was escorted to the bus, well-wished, words exchanged on my account, a rolled up bill pressed into my refusing hands. Then the doors were shut on us and Choum was left in the rear view mirror, the desert stretching flat around, the Adrar plateau a constant edge to the left. I thought of the cyclists who would cycle this road later today or tomorrow, flat and windy, and I thought of them again as the car went steeply up the sick-sack road taking us onto a plateau.

In Atar I was dropped off at the market. The town seemed pretty big and bustling, giving me hope on my first priority mission: to find an ATM, withdraw money and be in control again. Everything else would arrange itself once that was done.

With a little wandering around the center I found the first bank quite easily. I greeted the guard, wiggled my way inside the small ATM booth along with my backpack, fished out my bank card, wiped away sweat. Inserted the card. Followed the instructions. The machine spat out my card, displaying an error message. It’s OK, I thought. Sometimes ATMs in Africa do this. Sometimes you have to select a different amount. Sometimes they need another try. Sometimes it’s just my card. I repeated the process once. Twice. Three times. Finally I resigned, pocketed my card again, wiggled back out and asked the guard if there were any other banks nearby. He pointed around the corner and down the road and I began to walk.

At the next bank I chatted with the guard while waiting. When my turn came up I went into the little room and inserted my card. Once, twice, three times. No luck. I gave up just as an older man swept out of the bank in his darra’a. He eyed me through his glasses, low on his sharp nose, and greeted me calmly. I said hello. He asked briefly of my origin, then told me about his auberge in case I was looking for a room. I sighed and smiled and explained my situation to him: I had no money and was yet to find an ATM that would work for me. He listened, then offered to drive me to the next bank.

“And if that one doesn’t work either, you can come and stay in a room at my auberge, free of charge,” he told me.

“You will eat with the family.”

Feeling both moved and resigned I pushed my backpack into the back of his four-by-four, then got into the front. What else would I do? As much as I disliked to keep relying on kindness like this, as much as I wanted to be free already and have the means to pay for my stays, his offer was my best option; I really didn’t know what I’d do or how I’d spend the night if my money remained numbers on a screen when I needed it to be paper in my pocket. Might as well rely on this kind-seeming stranger.

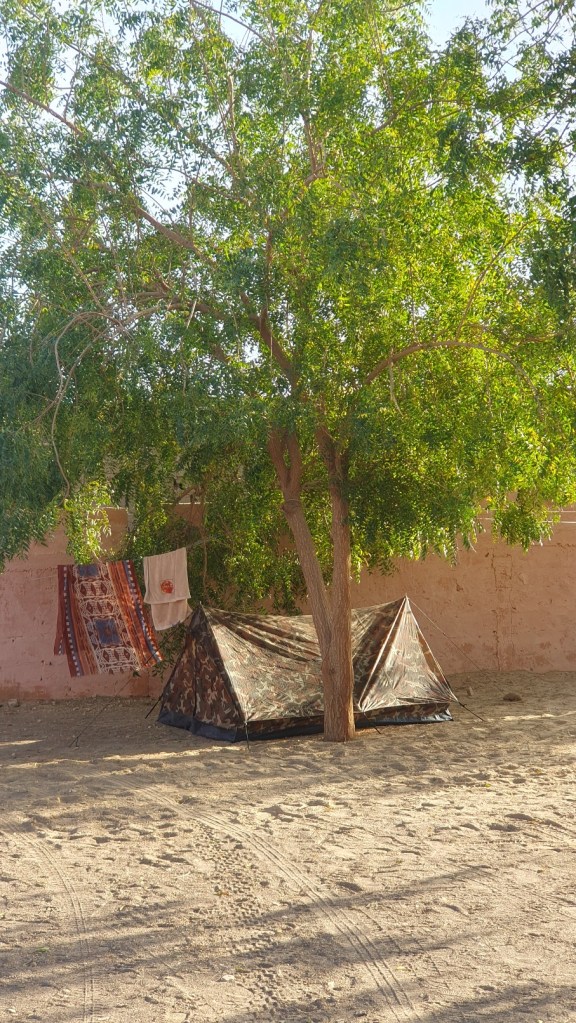

Sidahmed’s auberge was at the outskirts of Atar. On opening the painted iron gate we entered a small yard surrounded by low buildings. A big tree stood in the middle and a cottage of palm leaves was woven around its trunk. Doors led to single rooms and I was offered one but declined and decided to pitch my tent in the shadow of a smaller tree. A small room in the corner of one of the buildings lacked doors and I was introduced to the men lounging inside and drinking tea: a man working at the auberge, a colleague who ran another augerbe out by a nearby oasis and Sidahmed’s brother. I was offered tea while I explained my situation and everyone immediately engaged, offered advice and asked questions. I was tired. Yes, I had already tried that other ATM, I had tried three of them. No, neither of them had worked. Yes, I had tried asking for different amounts. No, I don’t think there is a point in trying them tomorrow, sometimes it just is like this, it’s my card, it’s a foreign bank. Were there any applications I could use for international money transfers?

They all shook their heads.

I sighed. For the moment I was good, all was well; I had a place to stay and was invited to share the meals. I had secured a place to stay in Nouakchott and would just go there if this didn’t resolve – surely I could hitchhike! – but oh how I wanted to be free of depending on people’s kindness, having them serve me with my hands hanging at my sides. Having received so much already, I felt the scales tip way out of balance, my skin starting to feel itchy with guilt. I should give.

We sat for hours discussing my problem. Some of the men made phone calls and texted friends for advice on what to do. I let it happen, grateful, resigned. I downloaded a handful of apps that didn’t work. I was promised to be taken to the bank office on the next day.

Darkness fell around the auberge. The shadows seemed deeper here. Mosquitoes started biting my ankles, silent and invisible. Sidahmed’s wife brought a plate of food and I sat around it with the men, the only one holding a spoon and the one to finish last. The pasta mixed with meat was simple and delicious. They laughed at me and my slowness;

“The hand is bigger than the spoon,” they teased.

Crickets sang loudly. The few other guests had either retreated or kept low conversations. I retreated into my tent under the tree, struggled out of my malefha in the crammed space and into my sleeping bag. Again, my mind shifting into the state of taking one day at a time, leaving problems hanging until they could be resolved, trusting that at some point, somehow, they would. For now my belly was full and I had a place to sleep and that was enough.

…

The way back to the market was long, but I had barely stepped out onto the main road before a car slowed down by my side and offered me a ride. I explained to him that I could not pay and he simply shrugged and said that it’s OK. I got in.

Atar is flat with a lively market at its center and the sand streets getting more and more quiet the further away from the market they are. The Adrar plateau is a curious edge running along the eastern horizon. People eye me with calm curiosity but do not approach; it’s not like Morocco, with men tailing me and insisting on my number, tiresome however friendly. Here none of that. Wearing my malefha I don’t attract attention until people see my face, which helps. I ask for the price of a kilo of mandarines and the man next to me, just finishing up his purchase, buys a kilo for me. We chat briefly and he asks for nothing as we part ways. Everyone remains calm and friendly towards me; eyes might linger on me and in mine, but no one intrudes. I relax. On my way back the same procedure: a car stops without me asking and offers me a ride. This time I thank and decide to walk, despite the sun. An hour later I close the painted gates behind me, am greeted warmly by the men at the auberge and in turn I offer mandarines.

…

I don’t want to linger at how tedious and annoying, how long time it took to solve my cash-issue; in the end we solved it. I was constantly accompanied, always spoken for. Like a child, a foreigner-child, my discomfort balanced by my wish to get it fixed. After going to the same ATMs again, after meeting with several people at the bank, after asking everyone, finally, I asked my friend in Nouakchott. A man whose face I’d never seen but who’d helped me on more than one occasion already. I asked for his advice and within ten minutes I had the right application installed, sent the money to him, he in turn sent it to Sidahmed’s brother who withdrew it and placed it in my hands. Relief.

The relief of being free at last; I could do what I wanted now. I could go where I wanted, eat what I wanted, take tours if I wanted, pay my way out of the guilt of taking up people’s time. (I made a note to my self to take a closer look at that reaction.)

I could go anywhere;

I decided to stay at the auberge in Atar.

…

(This story told in pictures.)